Roll first, think later

On fortune-positioning and fortune-telling

There’s a fascinating phenomenon I observe every time I play with beginners.

Of all the unwritten rules new players are expected to grasp through play, a very common one is when to interject their narrative with a dice roll. Sure, most games have a variation of “describe what you want to do, and then roll the dice to see how it goes,” but exactly when one should stop narrating what happens and let the dice tell part of the story is more of an art form.

I usually see beginners falling somewhere between one of two ends of the spectrum. There’s either:

Player: “I swing my sword at them and cut them in half, and I look around, and the princess has fallen in love with me.”

GM: “Wait, wait, wait. Let’s, uh… start with the attack roll first. How about that?”

Or:

GM: “It’s your turn.”

Player: “Oh.” *rolls a d20*

GM: “Wait, wait, wait. What are you even trying to do?”

It usually takes a few rolls (or a few sessions), but once we grasp that timing, it becomes so second nature that any game that subverts that norm feels… weird.

Well, it just so happens that I love weird.

The misfortunes of fortune

When I say “norm” above, I’m oversimplifying. Different games have different moments when you’re expected to stop and roll the dice. Even within the same game, different types of action might call for different timing in rolls.

This “dice roll placement“ is what is normally referred to as fortune positioning, and if you search online for “fortune in the middle”, for example, you’ll find… well, contradicting definitions. But that’s beside the point. What’s important is that fortune positioning determines at which point in the trajectory from declaration of intent and narrated outcome we stop to check the dice (or any form of resolution mechanic, really).

Traditionally, players learn when and how to do it by experience—observing their friends, absorbing table culture, and getting it wrong a few times until they get a feel for it.

For some actions, it is easier to tell the right moment. If you are using a specific ability, there’s usually a well-defined order in which things happen. You say, “I’m going to activate my Soul Blast” or whatever, and we go, “OK, roll, and then we see what happens.”

Things get murkier when there’s no hard-coded procedures, like social situations in trad games. You perform that incredible speech but roll poorly—now what? Do we undo what you just said? Do we make some mental gymnastics to justify why it didn’t land? Should you have gotten a bonus because of your roleplay? But if your character is not very charismatic in the first place, should they have even been able to articulate such a compelling argument? Endless discussions over this topic alone have filled forums for the past decades.

Even when games have a much clearer instruction about fortune positioning—like PbtA games, which literally have a trigger for every move—it is still an acquired skill to understand when to shut your mouth and say, “Well, I guess we have to roll now, right?”.

Fortune at the extremes

There’s no one solution for that situation, because, at least for me, it is not a problem to begin with. I see it instead as a fertile ground for experimentation.

I’ve tried different approaches for fortune positioning with my games, and I especially like to push the needle beyond what’s usually considered the far ends of the spectrum. Let me explain what I mean.

See, when people describe “fortune at the end”, it usually implies that you describe everything that your character is able to do to affect the outcome, then you roll the dice, and then narrate the result. But what if you narrated even the outcome before you rolled the dice?

That’s what I did in Insurgent. The game says:

Regardless of your result, everything you describe happens exactly how you describe it. The roll of the dice determines the fallout of your action.

See, the dice don’t determine whether you succeed in your intended action. Instead, you describe the whole action beforehand, including its result.The dice inform the consequences of your action. A “fortune at the very end” kind of roll, perhaps?

At the other end of the spectrum, we have “fortune at the beginning,” which is usually described as rolling right after a declaration of intent and approach, using the dice result to inform what and how it happens. But… can’t we go even further back? What if we rolled before we decided what to do?

Fortune at point zero

That example at the beginning—the player enthusiastically reaching for the dice and rolling even before clarifying their intention—always stuck with me. What if we didn’t try to stop it, but instead leaned into it as the intended behavior?

For that to work, I figured that the system would have to follow these criteria:

All rolls in the game should be the same.

A roll is expected to be made at every turn.

There should be meaningful choices after the roll is made.

I finally managed to pull it off in my latest release, Load the Simulation. Let me show you how I followed these criteria and why I believe it works.

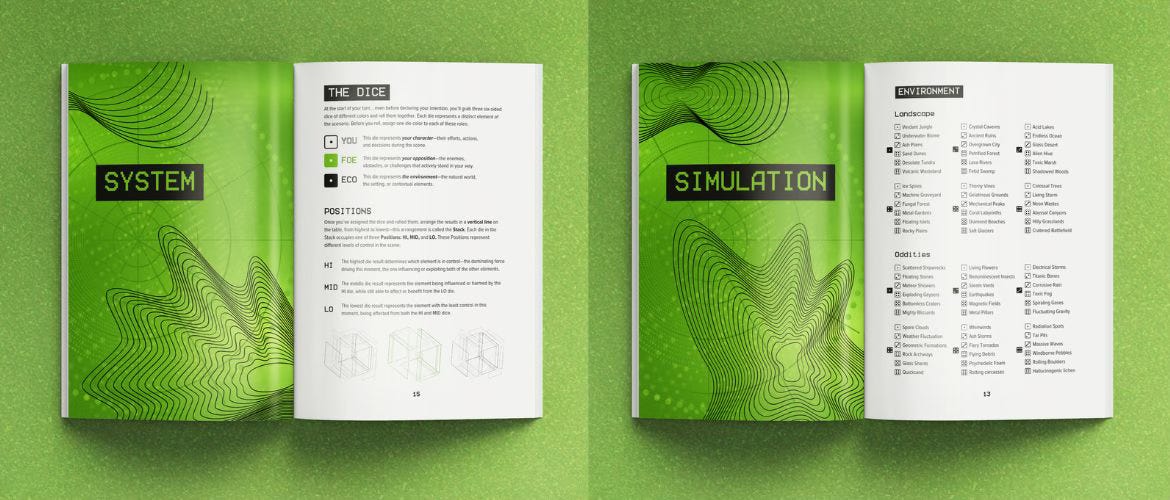

At the top of your turn, before you even think about your action, you grab 3d6 and roll them. It’s always 3d6, and there are no modifiers. If you had attributes, skills or actions that indicated different modifiers (like d20 systems), dice pools (as in Blades in the Dark), dice sizes (as in Savage Worlds), or dice pools and sizes (like in Cortex Prime), that wouldn’t work. You’d at least need to declare your approach before rolling. I didn’t want that, so all rolls are the same (meeting the first criterion).

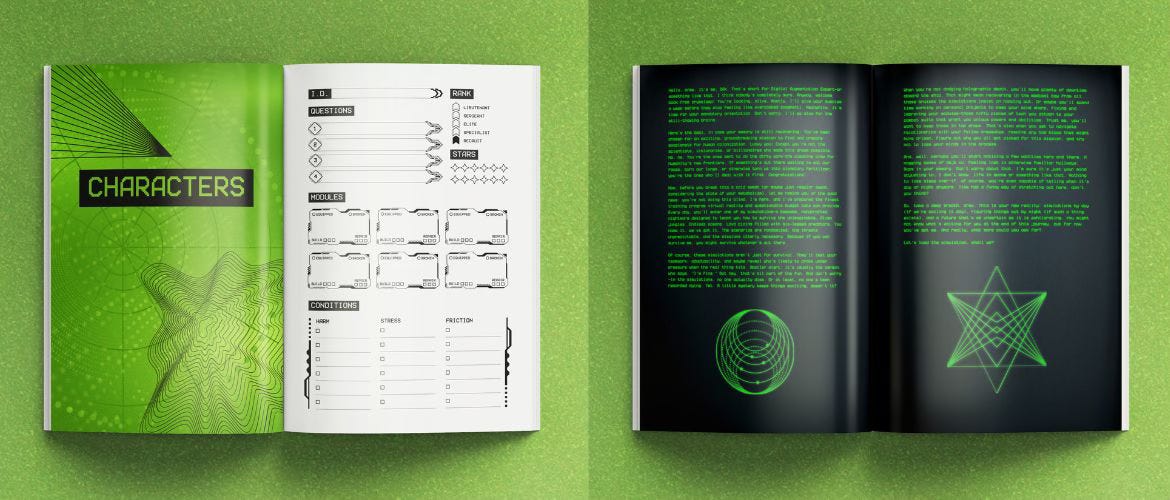

These rolls happen during the training exercise—your character is on a centuries-long mission to prepare exoplanets for colonization, and you’re going through training simulations (think The Matrix, X-Men or Star Trek). Since every turn represents an attempt to progress toward your mission objective, a roll is always required (meeting the second criterion). In a more open-ended scenario, that assumption wouldn’t necessarily apply.

What if we didn’t try to stop it, but instead leaned into it as the intended behavior?

Each die represents something different:

• The YOU die – Your character’s effort.

• The FOE die – The opposition.

• The ECO die – The environment.

You roll them together and arrange the results in a vertical line on the table, from highest to lowest— the Stack. The die with the highest roll determines the dominant force in the scene. If the YOU die is not the highest, you’ll take Conditions. You have to choose whether to affect:

Your body (Harm) – Bruises, burns, or worse.

Your mind (Stress) – The slow wear of fear and pressure.

Your relationships (Friction) – Putting crewmates in danger, failing to have their back, or blaming them for your mistakes.

You can also choose to break one of your modules to avoid a condition, or use them in the scene to break a tie. So there’s this short mini-game you play after you roll to determine the mechanical implications of your roll (the third criterion).

With all the mechanical bits resolved, you’re left with a scene to paint. The roll generated a lot of input, and you can create a rich narrative that won’t later be contradicted by a dice roll.

Say the ECO die is higher, and you marked Friction. How does the environment take central stage, and how does that affect your bonds with your crewmates? Perhaps a tremor opens a giant crack in the ground, you grab your friend by the arm to keep balance, but end up sending them tumbling down near the edge of the cliff. That is… so much fun!

You get to look at the dice as a fortune teller reading runes, and extract juicy, colorful fiction from the results. You decide if you’re in a more active position, taking the lead and making progress, or in a more reactive one, trying to resist this alien world that is trying to crush you.

See, it is not that you are abdicating control over what your character does by rolling before deciding. You still have total freedom of choice, but you’re informed of the outcome beforehand, so you get to frame that snippet of a scene, including actions and reactions, in a vivid way that incorporates everything you accomplished and everything you suffered in the process. And I think that’s neat.

There’s more nuance to it (each combination of dice position has different mechanical ramifications), but that’s the gist of it. I’m certainly not the first person to think of the roll first, think later approach to resolution mechanics, but I am really excited about how I managed to implement it in Load the Simulation.

If you want to learn more about this game of high-octane training simulations and intense interpersonal conflict, the crowdfunding campaing started today (and there’s a limited Early Bird discount, so check it out).

Enjoyed reading about your thought process behind the mechanisms. Good luck with the crowdfunding campaign!

love the way you think about this stuff. the 3 dice positionings is a really interesting model.